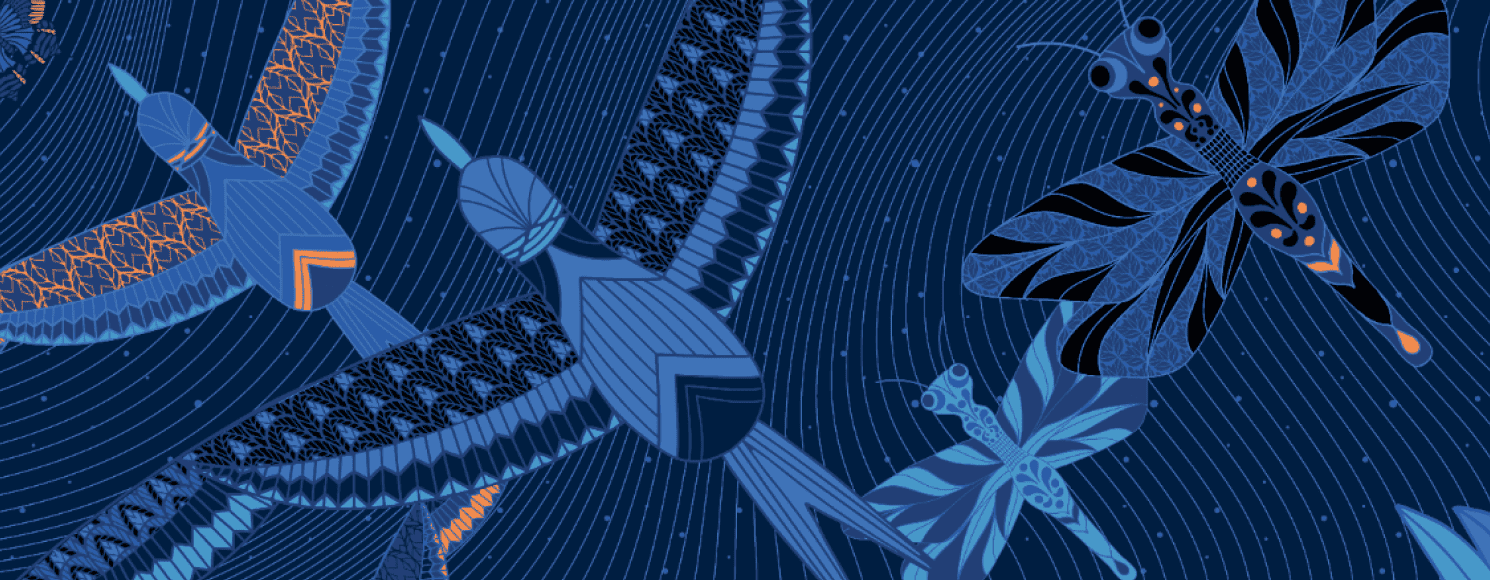

«Charlotte Perkins Gilman escribió El papel pintado amarillo, clásico gótico y feminista, después de una depresión posparto —nadie la llamaba así entonces, a fines del siglo XIX—. Imaginó a una mujer encerrada en una casa y atormentada por el papel de su habitación, que describe mucho, en detalle, como algo opresivo, vivo, amenazante, un reflejo de su claustrofobia y su desdicha. Laura Varsky, con inteligencia, la desobedece: ahí están las flores con sus espinas, las manos de mujer que se asoman, la intensidad intrincada de los detalles del papel; pero no hay nada ominoso, solo triste, en esa mujer atrapada que se tapa la cara con las manos, que se hace una con el amarillo, que cuando no está en posición fetal se aferra a los barrotes que no la dejan morir.»

Mariana Enriquez

«Charlotte Perkins Gilman penned ‘The Yellow Wallpaper,’ a classic piece that intertwines gothic elements with feminism, following a postpartum depression—though it wasn’t labeled as such in the late 19th century. She envisioned a woman confined within a house, tormented by the wallpaper in her room, which she vividly describes as something oppressive, alive, and threatening—a reflection of her claustrophobia and misery. Laura Varsky, with intelligence, disobeys this portrayal: there are flowers with their thorns, women’s hands peeking through, the intricately intense details of the wallpaper, but there is nothing ominous, only sadness in the trapped woman who covers her face with her hands, who merges with the yellow, who, when not in a fetal position, clings to the bars that won’t let her die.»

Mariana Enriquez